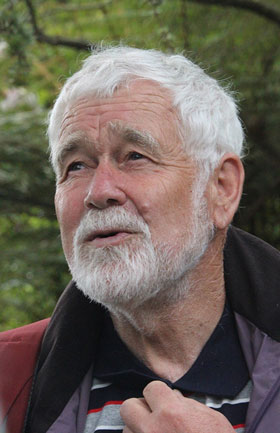

Widely known as one of the leaders of biosecurity in New Zealand, Dr John Hellstrom’s involvement in the industry spans almost half a century. The GIA Secretariat caught up with him following the conclusion of his role as chair of the GIA interim FMD Council, to talk about the changes he's seen during his career, and get his views on New Zealand's biosecurity system.

Widely known as one of the leaders of biosecurity in New Zealand, Dr John Hellstrom’s involvement in the industry spans almost half a century.

Dr Hellstrom is a pioneer of biosecurity in New Zealand and is probably best known for his work as Chairman of the Biosecurity Council and as Chief Veterinary Officer for MAF. He was instrumental in developing the 2003 Biosecurity Strategy; he’s established new systems for protecting native plants and agriculture from pests and disease, and for animal welfare in New Zealand; but his proudest moment is getting a Kakapo on the cover of the 2003 Biosecurity Strategy.

The GIA Secretariat caught up with him following the conclusion of his role as chair of the GIA interim Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) Council.

You’ve been called the father, or maybe grandfather of biosecurity in New Zealand. Tell us about how you’ve seen the approach to biosecurity change over the years.

Conception in the public sector tends to be by committee. Our biosecurity system has several parents. Royce Eliot, DDG of MAF 1986-92, was the first to advocate for a single system for protecting agriculture from exotic threats and the Hon Simon Upton, Minister of Biosecurity in the mid-90s, was the first to envisage a single system to protect all our biological resources. My contribution was to help build the system for them and find a name for it. Many others were involved in the early days: notably Richard Ivess, Chris Boland, Derek Robinson and Ruth Frampton. As the last one standing I’ve inherited the grandfather title.

The greatest changes have been a much more sophisticated approach to risk management, much more efficient use of resources and the greater involvement of all New Zealanders. All of these are still themes for continuing improvement but when I look back I can see how much better we are at doing these three things now.

You’ve had an interesting career to date, tell us briefly about how you got to where you are now?

I’ve been involved in biosecurity for almost 50 years. I was lucky to have been involved in the very early days of the bovine brucellosis and tuberculosis eradication programmes. We learnt so much from these very successful programmes and from the mistakes we made in them too. For example, my response to those who say we should walk away from the end of the Tb scheme, is to say ‘we tried that experiment in 1980 and it didn’t work’. Instead we’ve spent about half a billion dollars to repair the damage caused by stopping possum control too soon.

I was also closely involved in the debate about the risks to New Zealand from scrapie in sheep and mad cow disease and learned how much we can be misled by experts who make guesses based on inadequate knowledge. We were very lucky to not get scrapie because some experts saw the benefits of improved sheep genetics as greater than the harm that might have been caused by the disease.

My time in the animal vaccine industry was interesting because to my surprise their approach to risk management of commercial threats was much more sophisticated than I had expected.

The most important opportunity I got was being asked by Simon Upton to act as the independent chair of the Biosecurity Council and lead the delivery of his vision for a single system to manage biological risks to New Zealand. That culminated in the publication of the highly successful 2003 Biosecurity Strategy. After that I’ve had another decade of interesting consultancy work in biosecurity, both here and internationally.

You’ve been the lead peer reviewer for the B2025 review, and have been facilitating the Foot and Mouth Disease Council (FMDC) to help its members move towards joining GIA. Tell us what you think the future holds for biosecurity in NZ.

I think there are a number of important forces that are going to determine that future. How well we deal with those forces is going to provide the answer to your question. Our heavy and growing dependence on trade and tourism to support our lifestyle is putting incredible pressure on our risk management systems. We have to become more and more responsive to changing risk profiles and employing the most effective and efficient tools to manage them. New Zealand really has no option but to be the world’s greatest innovator in biosecurity and I believe we are really building momentum in being truly creative. The need for innovation is more than having a better understanding of risks and better tools to fight them but also for innovative ways of governance and getting everyone involved.

What’s your advice for government and industry to improve biosecurity in NZ?

Share power. We still have a long way to go to get the broad range of ownership we need to get really good outcomes. Bureaucracies are not good at innovating. We need constant effective and efficient innovation in system design. I see GIA as an important step in working towards a much greater system resilience. I’m pleased to see that government is now moving towards a more open approach to power sharing, but in my view, there is still a long way to go. Industry also needs to step up and assert its role.

What’s the biggest impediment to progress?

I see two. Managerialism, resulting in the loss of technical knowledge at the decision-making levels, is the biggest impediment. Sound biosecurity planning and response requires competent technical scrutiny of options as well an analysis of political and economic risk. Our tools for economic risk analysis are also unhelpful for many decisions in biosecurity, particularly decisions related to response, where investment costs occur up front and impact costs mount a lot later. Traditional approaches to cost benefit analysis can discount major future harms out of the investment portfolio.

What has been your proudest moment in your career so far?

I felt I had achieved Simon Upton’s vision of a single system when I succeeded in getting a Kakapo on the cover of the 2003 Biosecurity Strategy. It was very important to me personally because I thought it made it clear to everyone that biosecurity wasn’t something that could be done in isolation from society. It had to respond to social and cultural values if it was going to work properly. Society as a whole is more motivated to protect indigenous biodiversity than primary industry so this is a powerful way of engaging them.

In terms of biosecurity, what’s been the biggest change you’ve seen the industry go through?

Rogernomics pulling the pin on agricultural subsidies. Suddenly a whole range of biosecurity services that had been provided by the State were closed down or transferred to industry management and user pays. Pest and disease control suffered most but surveillance and response capability were seriously weakened for several years until new industry-led or industry supported initiatives replaced them. This was imposed on industry with little planning or insight and we were lucky to get through with so little harm.

You facilitated the FMD Council to help them develop an OA for FMD. Tell us about that?

We thought that developing an FMD OA would be the best pathway to engaging the pastoral sectors in GIA. I was particularly impressed with the efforts of the working group we established. They worked hard and collaboratively but needed stronger support from the council for the OA process. In hindsight I think FMD was the wrong place to focus. Its potential impacts are so huge that they almost over-ride the collaborative intent of GIA. I nevertheless very much enjoyed working with the Council members.

Do you feel that industries can work together in partnership under the GIA model? Do you believe it will lead to improved biosecurity?

Yes and Yes. But as I have said before there are problems. Risk management for plants and animals to some extent goes down different paths and there is potential for disagreement over priorities based on these differences. However, a broad industry membership of GIA will oblige government and MPI to take much more serious account of industries’ concerns. I also believe that increasingly the technical awareness of risks and how best to manage them is going to be based within industries rather than within the bureaucracy. Industry participation is critical to better biosecurity.

In your view, what would be the perfect biosecurity model?

I think that governance is the key. Biosecurity has such major and diverse significance for New Zealand that governance must recognise the responsibilities, interests and abilities of all stakeholders. So my perfect model sees the biosecurity system being managed by a single agency (and I don’t mean a standalone agency, there are major efficiency and effectiveness benefits from co-locating biosecurity, food safety and promotion of primary industry). But with broader governance oversight involving the other key stakeholder areas of concern such as protection of biodiversity and pest management. There are invariably going to be times when economic, social, cultural and environmental considerations are going to seriously conflict and I believe it is unreasonable to expect MPI to resolve those conflicts on its own.

What next for you?

My biosecurity interests are going to become much more local. I have been appointed as a guardian of the Kaikoura Marine Sanctuary to provide a biosecurity perspective and am actively involved in the governance of conservation projects throughout the Marlborough Sounds. I’m also chairing the Totaranui 250 Trust, which I’m preparing for commemorating the sestercentennial of James Cook's voyages of discovery and the first meetings between Maori and Europeans in the 1770s. So I’m not planning on being bored.